The History of a Czech Photographic Legend

Langhans Ateliér, founded in 1876, became an icon of Czech portrait photography. Although the archive of this renowned studio was destroyed in the 1950s, the rediscovery of part of the collection in 1998 and 2000 offers valuable testimony to the lasting significance of the Langhans legacy for both Czech and European culture.

The History of Langhans Ateliér

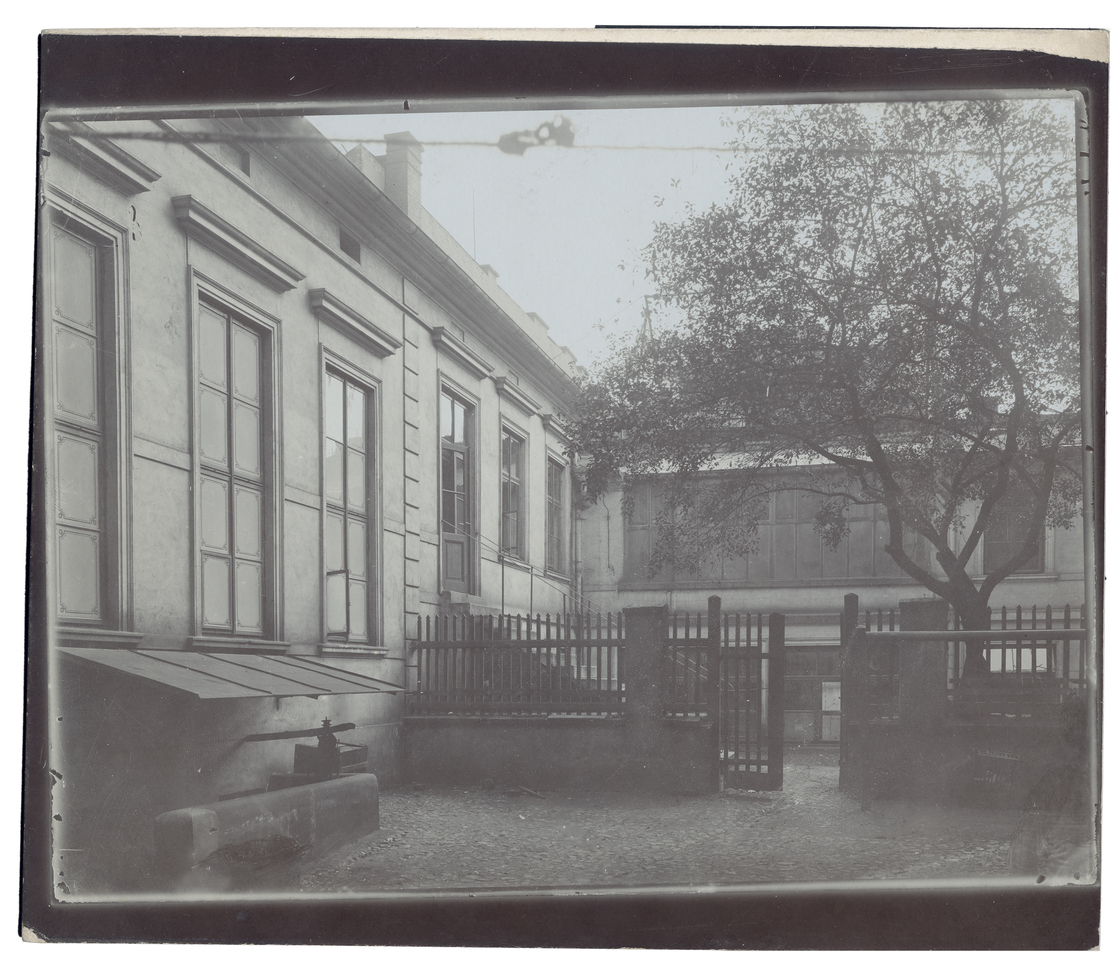

Jan Langhans (1851–1928) studied food chemistry, but his personal interest led him to photography. In 1876, he opened his first modest studio in Jindřichův Hradec, where he worked during the summer months. Four years later, in 1880, he moved to Prague. In Vodičkova Street, he founded a portrait studio that quickly became the largest photographic business in Bohemia. Jan Langhans was chairman of the Czech Photographic Society, took part in national and international exhibitions, and received numerous awards and honours (including from the Persian Shah and the King of England). In 1919, he handed over the running of the Langhans Ateliér to his daughter and her husband. He died in 1928.

Langhans Ateliér was renowned for introducing technical innovations, for its exemplary craftsmanship and artistic execution, and for its bold marketing for the time. It soon became one of the most sought-after portrait studios in Bohemia, thanks to its innovative approach to photography and advertising, and its high quality standards. By the end of the 19th century, the Langhans Ateliér was producing tens of thousands of photographs annually—not only portraits, but also landscapes and documentary images.

Expansion of Studios Across the Country

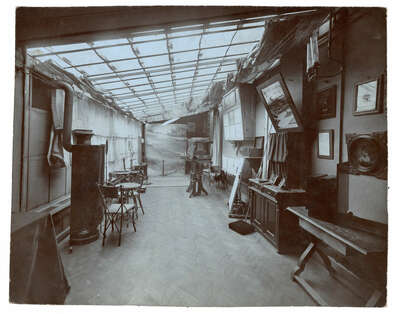

Langhans Ateliér thrived not only due to the quality of its work but also through the expansion of branches across the country. In addition to its main headquarters in Prague, it opened studios in Mariánské Lázně, Plzeň, České Budějovice, Hradec Králové, and Náchod. Crucial to its success was Langhans’ constant embrace of new technologies. He was one of the first photographers to use electric lighting in the studio, allowing work even in unfavourable natural light.

Innovative Approach and Emphasis on Quality

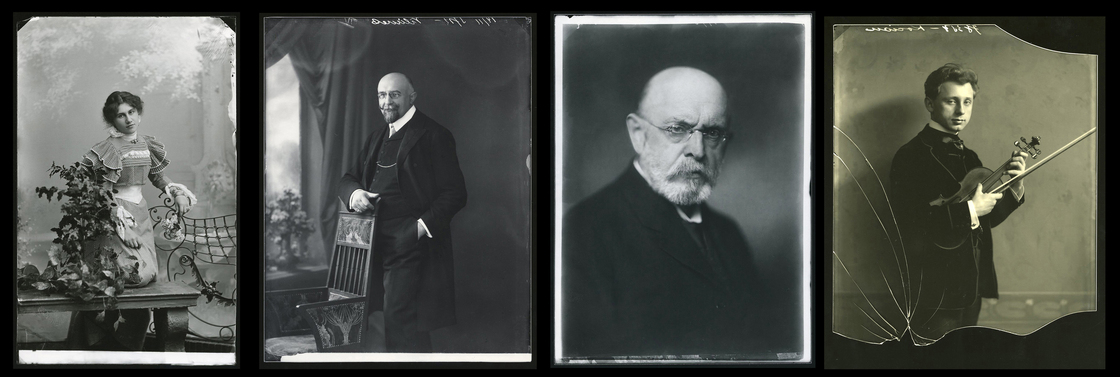

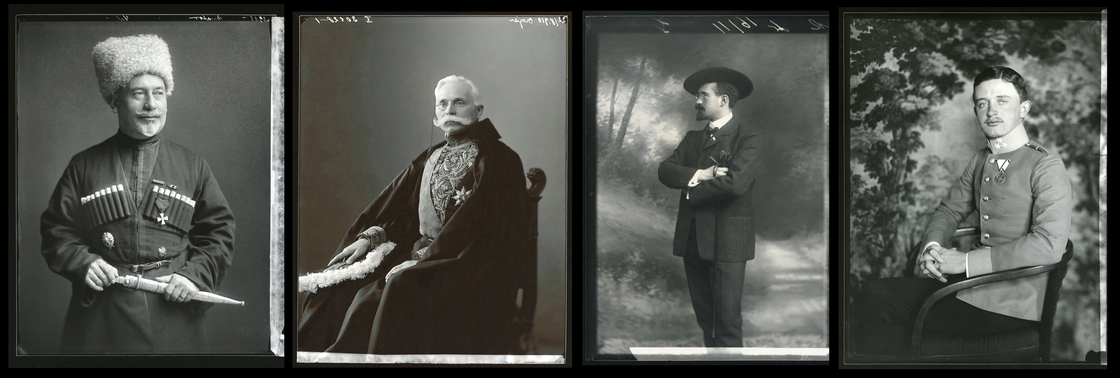

Langhans’ approach to photography was characterised by technical perfection and elegant presentation. The clientele included prominent politicians, scientists, artists, clergy, members of the Sokol movement, aristocracy, and thousands of ordinary customers—thus making portrait photography accessible to the wider public.

While other photographers focused primarily on artistic experimentation, Langhans built his reputation on precision and formality. His images had an official tone. He placed particular emphasis on lighting, posing, and meticulous retouching, resulting in noble and formal-looking portraits.

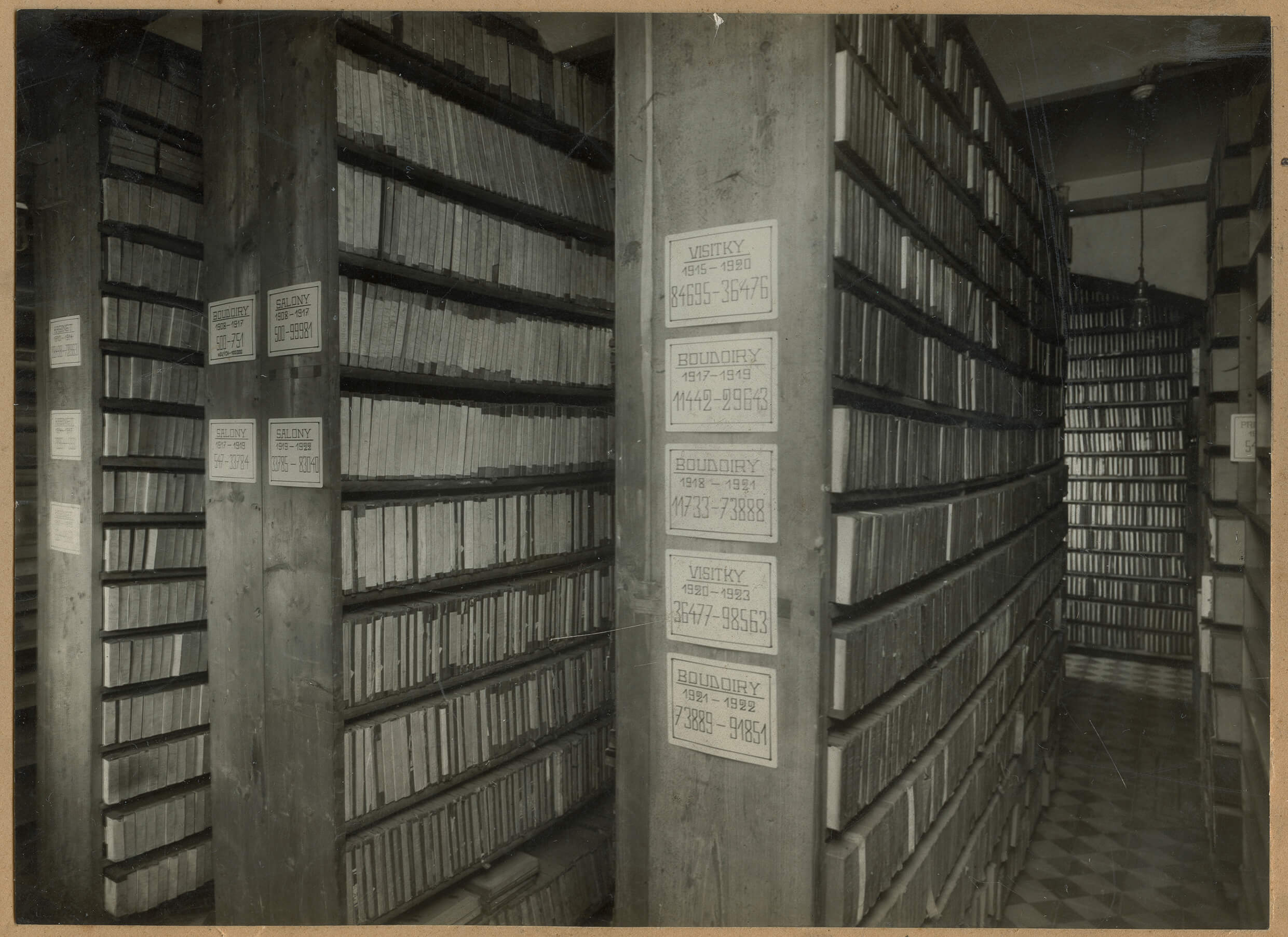

Company Archive

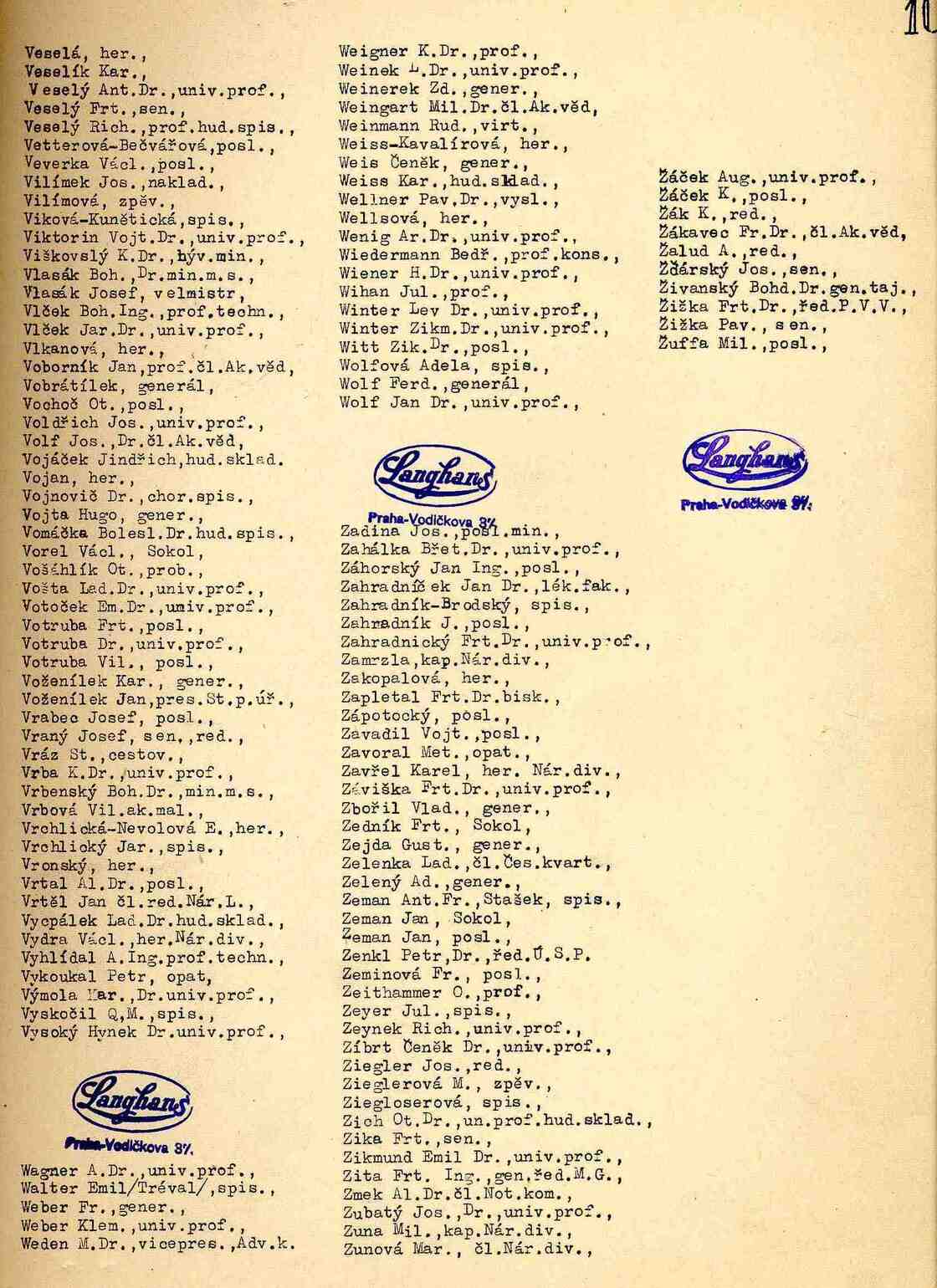

Throughout its existence, Langhans Ateliér carefully archived and catalogued negatives of all its clients. For decades, customers could request new prints of not only themselves but also their ancestors. Thanks to this methodical archiving, the studio held nearly two million negatives—mostly on glass plates—just before World War II. The Langhans collection was the largest photographic archive of its time.

The Gallery of Eminent People

From the founding of the studio in 1880 until its closure after 1948, portraits of significant individuals were carefully selected from the vast company archive. This selection was originally titled Our Archive of Eminent People, later known as The Gallery of Eminent People. It became a unique collection divided into categories by the profession of the subjects—actors and singers, politicians, writers, judges and entrepreneurs, visual artists, musicians, scientists, foreigners in Bohemia. This archive was a source of pride for the studio and a vast testament to the nation's elite.

Nationalisation

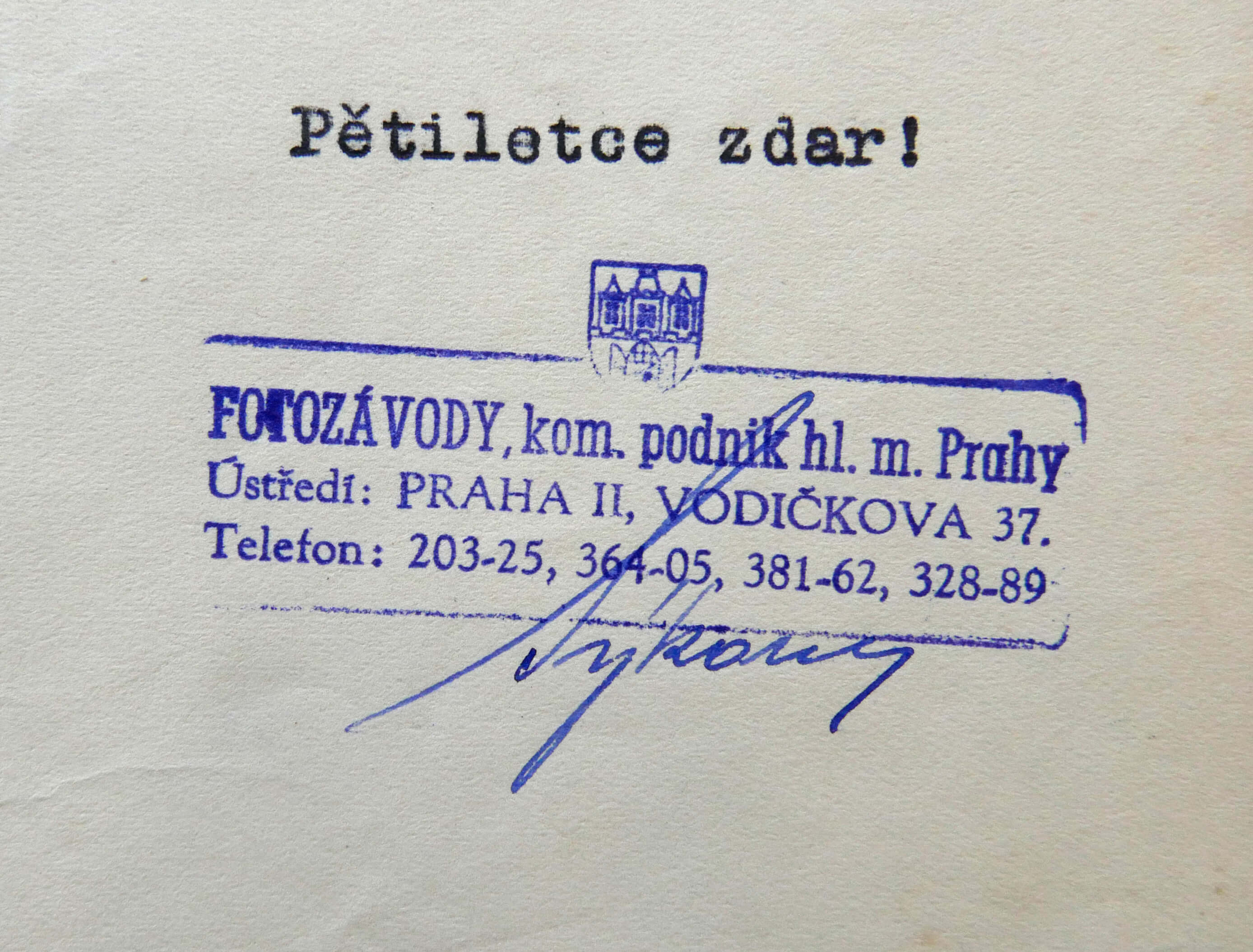

Following the communist coup in February 1948, a decree on the socialisation of services came into force, which included the nationalisation of the Langhans Ateliér. The house at Vodičkova Street 37 in Prague, including the studio's equipment, was taken over by the state and later operated by the Municipal Enterprise (and later the Photografia Cooperative).

Destruction of the Archive During the Communist Era

The most significant cultural loss suffered by Langhans Ateliér was the physical destruction of its enormous glass plate archive in the winter of 1951/52. All plates were loaded onto carts and then transported by truck to a landfill in Kyje near Prague. Within days, the portraits of both famous and unknown individuals—including prominent men and women—were reduced to tonnes of shattered glass.